This is the introduction to a new series of posts on our blog.

I recently posted about one of the most important debates in all of modern cinema, the struggle between film and digital. But there’s another equally-important conflict, one that’s a little older and a little deeper beneath the surface. This is the fight between two of the most integral components in a film: the image, or what actually appears on the screen, and the idea, or the initial concept that is developed into the narrative content of a film. At one end of this spectrum you have pure cinema advocates like Stan Brakhage, individuals who believe that cinema should be an art separate from all other narrative forms, while on the other side you have those who view filmmaking purely as a vehicle for storytelling. The modern director who most exemplifies the latter is, in my opinion, Christopher Nolan, a director so concerned with the intricacies of his plots that he barely gives any thought to the visual geography and mise en scène of his own films. This post is the introduction to a series I will be publishing over the next few weeks, in which I hope to outline my thoughts on these two approaches to the cinema, henceforth referred to as “image cinema” and “idea cinema.”

In my own personal opinion, I often feel the importance of image cinema is drastically understated in modern moviemaking, so I hope to advocate for more of a return to these basic principles. I’ll be outlining the works and artists I believe most represent these two separate philosophies, and then analyzing the facts before us to see which one is more effective. But first, let’s define these two terms.

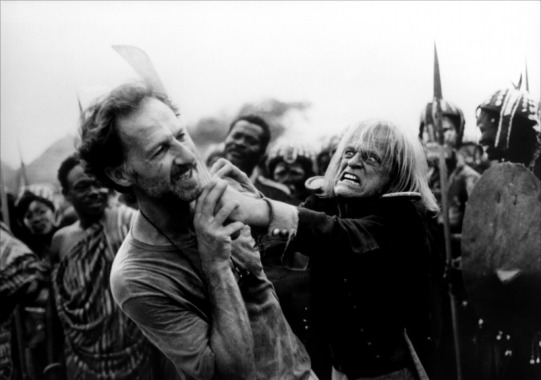

Image cinema is focused most of all on the actual content of the screen. Let’s not confuse this with the movement of the camera, although this does play a role. Rather, it concerns what we see and how we see it, so production design and art direction, camera placement, and the subject itself play an incredibly important role. If I had to pick a director to represent the “imageists,” if you will, it would be Werner Herzog, as he is devoted solely to the creation of new images above all else. Actually, it seems that a long history of “image cinema” can be traced through German cinema, and I’ll be analyzing this trend through a bit of a Godardian lens in a later post. (A note: Image cinema films can be detailed in their plots, but the image takes precedence over the story’s content.)

Idea cinema focuses on telling a story, or exploring the intricacies of plot construction. The most visible examples of idea cinema fall into two categories: a) films concerned mainly with communicating the details of a story and b) films that explore the construction of plots and stories, such as Nolan’s films, movies with plot twists, hyperlink narratives, and some meta-films. But meta-films can get a bit confusing and difficult to pin down, as they stride the line between image and idea (Leos Carax’s recent Holy Motors is a perfect example).

I’ll start the series in my next post with a brief primer on idea cinema. I’ll try not to let my dislike for Christopher Nolan infect it all. So let’s roll out, yo.